Mistletoe dispersal

How did some mistletoes get to remote islands ?

As we have seen, mistletoe dispersibility is limited by the short time the seeds spend inside their specialized fruit-eating birds, and by the birds’ erratic local flight patterns. Dispersal distances are commonly metres rather than kilometres, and mistletoes consequently have dispersed almost exclusively over land rather than water, and have continental distribution patterns. As mentioned above, mistletoes have not recolonized Tasmania since its last isolation from mainland Australia some 15,000 years ago. In Indonesia the mistletoe species which are widely distributed over several islands are lowland species which probably dispersed at times of lowered sea level, whilst species of the highlands are often narrow endemics. In our own region land connections across Torres Strait have been made and broken by sea level change several times in the last 100,000 years, and many mistletoe species are common to New Guinea and Queensland.

Around the western Pacific Rim there are c. 400 species of Loranthaceae with essentially continental distributions. The few species which do not fit this pattern are therefore very striking.

The most spectacular of these is Decaisnina forsteriana (right). The other 24 species of the genus fit the general continental distribution pattern (below left), but D. forsteriana ranges from the Louisiade Archipelago off the eastern tip of New Guinea eastwards to the Solomons, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, the Cook and Society Islands and the Marquesas (below right). In this band across the tropical southern Pacific distances between recorded occurrences sometimes exceed 1000 km and even reach 2000 km.

|

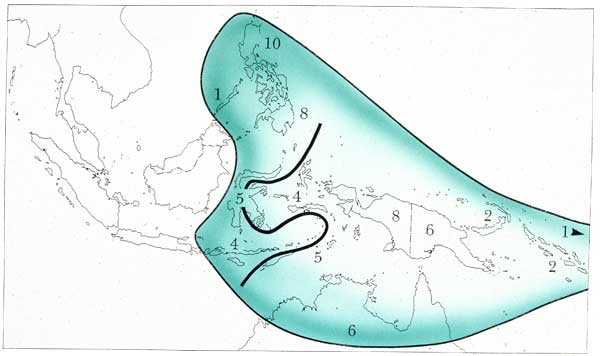

Map above shows the extended range, in red, of Decaisnina forsteriana

Map left, shows the distribution of Decaisnina with the number of species. |

There are a few other mistletoe species in the Pacific with apparently waif distributions, although less spectacular. The three species in New Caledonia, Amyema artensis, A. scandens and Amylotheca dictyophleba ![]() , are all found in New Guinea as well, and one of these, A. artensis, also extends to Vanuatu, the Caroline Islands and Samoa.

, are all found in New Guinea as well, and one of these, A. artensis, also extends to Vanuatu, the Caroline Islands and Samoa.

A different pattern is shown by Ileostylus micranthus, a seemingly primitive species widespread in New Zealand. It is also present on Norfolk Island, 700 km to the north, in a small but conspicuous population near the summit of Mt Pitt, the frequently visited highest point on the island. Fruit set is low, and the population is barely sustaining itself. It is tempting to regard this occurrence as relictual, the outcome of postulated land connections along the late Tertiary Norfolk Ridge between New Zealand and Norfolk Island. However Norfolk Island has been subject to several thorough botanical surveys, and in those prior to 1900 I. micranthus was never recorded; in contrast it has always been recorded in subsequent surveys. It seems more likely that Ileostylus reached Norfolk Island by distance dispersal about 100 years ago.

Another example involves the eastern Australian species Muellerina celastroides ![]() , which ranges in open forests from the Queensland Sunshine Coast to the Lakes District in Victoria. Two collections of M. celastroides were made in the North Island of New Zealand in the mid-nineteenth century, but the species has not been found there since. Presumably there was a waif dispersal of M. celastroides eastwards to New Zealand, but the colonization there was short-lived.

, which ranges in open forests from the Queensland Sunshine Coast to the Lakes District in Victoria. Two collections of M. celastroides were made in the North Island of New Zealand in the mid-nineteenth century, but the species has not been found there since. Presumably there was a waif dispersal of M. celastroides eastwards to New Zealand, but the colonization there was short-lived.

There are no visible features of the fruits of these mistletoes which makes them different from their relatives. Moreover their easterly spread into the Pacific runs against prevailing winds and ocean currents. Some unusual bird dispersal events, rather than special adaptations in the plants, seems to be responsible for these exceptions to the usual mistletoe distribution patterns.

|

Likely candidates as dispersal agents for Decaisnina forsteriana ![]() and Amyema artensis include fruit-eating glossy starlings (Aplonis spp., see right) and trillers (Lalage spp.), which have radiated among the island systems of the tropical South Pacific as far east as the Cook and Society Islands. In Aplonis, 16 of its c. 24 species occur in island groups east of New Guinea. Other possibilities include fruit-doves (Ptilinopus, 20 spp.) and imperial pigeons (Ducula, 10 spp.). Both have reached the Marquesas, the eastern limit of D. forsteriana. They have been recorded as feeding on mistletoe fruits, and void seeds unground and intact.

and Amyema artensis include fruit-eating glossy starlings (Aplonis spp., see right) and trillers (Lalage spp.), which have radiated among the island systems of the tropical South Pacific as far east as the Cook and Society Islands. In Aplonis, 16 of its c. 24 species occur in island groups east of New Guinea. Other possibilities include fruit-doves (Ptilinopus, 20 spp.) and imperial pigeons (Ducula, 10 spp.). Both have reached the Marquesas, the eastern limit of D. forsteriana. They have been recorded as feeding on mistletoe fruits, and void seeds unground and intact.

Likely candidates as dispersal agents for Ileostylus micranthus and Muellerina celastroides include migratory cuckoos Chrysococcyx lucidus ![]() and Eudynamis taitensis

and Eudynamis taitensis ![]() , which are mostly insectivorous or carnivorous, but pass each year between New Zealand and Norfolk Isalnd, and the silvereye Zosterops lateralis

, which are mostly insectivorous or carnivorous, but pass each year between New Zealand and Norfolk Isalnd, and the silvereye Zosterops lateralis ![]() , which has dispersed naturally from Australia to New Zealand and Norfolk Island.

, which has dispersed naturally from Australia to New Zealand and Norfolk Island.

Unusual distance dispersal in mistletoes seems to be almost exclusively a Pacific phenomenon, and a shift in avian vectors seems the most likely cause. In continental areas the highly specialized and efficient mistletoe birds and other berrypickers may monopolize the supply of fruits, and because of the short time the seeds remain inside them, have a constraining effect on mistletoe dispersal. In the Pacific region, however, berrypickers extend no further east than the Solomon Islands. Beyond there they are replaced by other potential agents, such as the glossy starlings, trillers, fruit-doves and pigeons, which probably eat mistletoe fruits irregularly as part of a more general fruit diet, and which may not pass the seed for several hours, particularly if the rind is not removed from the fruit.

The unusual distributions achieved by mistletoes such as Decaisnina forsteriana are therefore probably the consequence of disruption of the mutualistic association between the mistletoe and its highly specialized berrypicker dispersal agents. When the fruits become exclusively available to more generalist feeders, including perhaps even maritime birds, dispersal and recruitment may be less efficient, but dispersal over longer distances more likely. The critical step may be a mistletoe range extension beyond the normal range of the mistletoe birds, which opens a window of opportunity for distance dispersal which is not normally available in the continental homelands. Mistletoe dispersal eastwards across the Pacific has probably been a sporadic process rather than a single event.

![An Australian Government Initiative [logo]](/images/austgovt_brown_90px.gif)